Financing Options for Small or Rural Hospitals

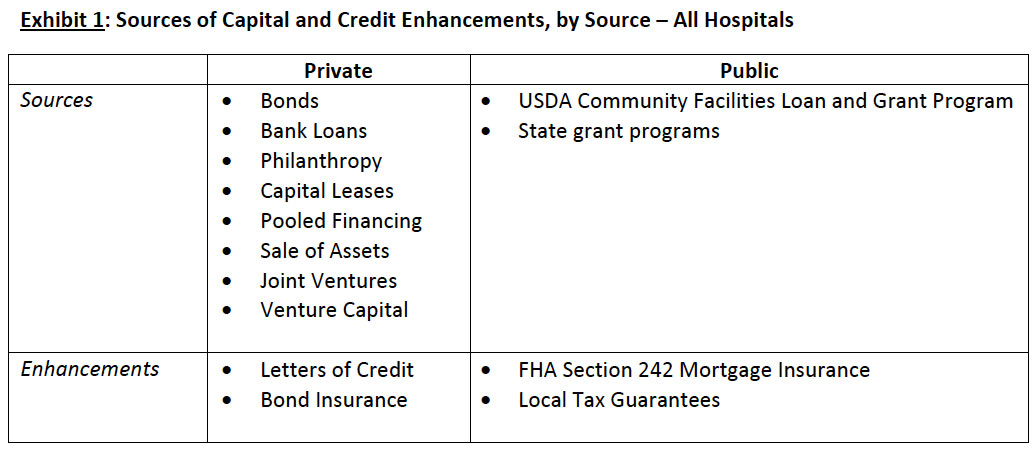

This article is Part I of a two‐part series. The purpose of the series is to highlight the capital financing options available to small or rural hospitals, including the risks associated with the most common approaches. Part I focuses on private financing sources and credit enhancements available to small or rural hospitals. Part II, coming in the October issue of BoardRoom Press, will focus on public financing options and the role of the Board in evaluating financing options. Marian Jennings will be speaking on related topics at the Governance Institute Leadership Conference on September 15th in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Introduction

There are more than 1,650 small and/or rural hospitals in the United States, including nearly 1,300 critical access hospitals (CAHs).1 These hospitals serve about one‐fifth of the U.S. population, and tend to care for more elderly and frail patients than do larger, urban hospitals.2 Because of their small size, and modest assets and financial reserves, these smaller hospitals face significant challenges in securing long term financing to meet their on‐going capital needs beyond what they can “save” from operating income.

Private Sources of Capital

1. Bonds

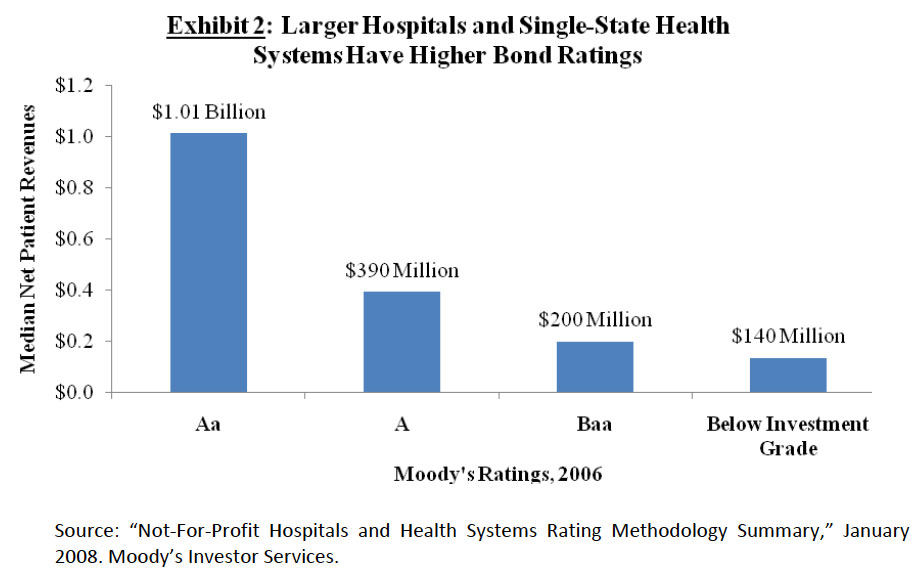

Small or rural hospitals affiliated with larger systems typically participate in an Obligated Group created by the system that then issues either taxable or tax‐exempt, publicly traded bonds, for which all members of the Obligated Group are jointly and severally obligated and liable. However, most independent small hospitals are unable to access debt through bonds because they are just too small. And small translates into greater risk to the bond holder. As indicated in Exhibit 2, the median net patient revenues associated with the lowest investment grade hospital bonds is $200 million. Many small or rural hospitals generate revenues in the tens of millions, not hundreds of millions. Small or rural hospitals are rarely able to access capital via bonds even with credit enhancements, either private or public.

In the rare case when it is feasible for an independent small or rural hospital to consider a bond issue, such bonds may be either tax‐exempt or taxable, depending on their intended use and the tax status of the hospital. In the case of tax‐exempt bonds, the bonds are typically issued by a governmental authority on behalf of the tax‐exempt hospital. Taxable bonds may be privately placed (issued by a private bank, including local banks) or underwritten in the taxable bond market.

For system‐affiliated small or rural hospitals, tax‐exempt bonds offer access to large capital pools at a relatively low cost. However, for most small or rural hospitals, bonds – even with credit enhancements – are simply not an option, based on the institution’s credit profile, financial strength, and inability to produce the operating revenue streams necessary to support such debt.

2. Bank Loans

Traditional bank loans, usually as real estate or equipment term loans, are a more common vehicle used by independent small or rural hospitals to access capital. Interest rates vary based on the hospital’s credit profile, and can be fixed or variable through the term of the loan. Usually, the capital available from banks and other financial services institutions is less than $10 million. In small or rural communities, the amount of the loan may be further restricted by an individual bank’s lending limits. However, despite this drawback, the involvement of a local bank in the capital financing structure may contribute community involvement in the capital campaign and increase local “ownership” of the project.

3. Philanthropy

Philanthropy and private gifts are most commonly used for specific expansions that can be associated with “naming” rights and a capital campaign. For small or rural hospitals, this may include a replacement facility. National grants from charitable trusts are highly competitive; local gifts are dependent upon many factors, including the overall financial well‐being of the local economy, the hospital’s own “public relations” efforts, and Board enthusiasm for the project. However, even under the best case scenario, philanthropy is often limited and unpredictable.

Although some rural hospitals have been hesitant in the past to ask for philanthropic gifts, raising money is essential for two reasons: one, rural hospitals need money to grow and develop services; and two, raising money helps build community “ownership” in the hospital.3

4. Other Sources of Capital

Non‐profit hospitals have a variety of other financing options from which to choose, each with its benefits and drawbacks. In our experience, the three most likely for small or rural hospitals are capital leases; capital pools often developed at the State level; and sale of hospital assets (e.g., sell the hospital to a for‐profit chain). However, your Board and management should be aware of all of the following and consider whether any of them is feasible in your situation:

Capital Leases: typically used for large equipment acquisitions, e.g., imaging and other diagnostic equipment. Most helpful for organizations requiring equipment that is frequently changed/updated. This form of financing can be expensive when its full costs are computed. In addition, this so‐called “off balance sheet” financing is frequently considered debt by lenders of all types.

Pooled Financing: typically offered under the aegis of a State Hospital Association or Hospital Authority for reimbursing hospitals for equipment acquisition, renovations, and in some cases land acquisition or construction. Under this vehicle, a group of hospitals essentially borrows “together” in order to create a financing pool that is large enough and has enough diversification among its participants to reduce the credit risk. Examples of state association bond pools are Michigan (Healthcare Loan Program), West Virginia (West Virginia Hospital Association) and Colorado (Colorado Health Facilities Authority).

Sale of Assets: typically via sale of assets to a for‐profit hospital company and conversion of nonprofit assets to for‐profit assets. In many cases, these converted entities may revert back to nonprofit status at a later date.4 Access to capital has traditionally been the number one reason that small or rural hospital sold to larger, for‐profit chains. Including the loss of local autonomy, the “costs” of this approach are great, although many system‐affiliated small and rural hospitals believe that they are stronger overall for having made this decision.

Joint Ventures: typically involving physician groups, in an effort to align incentives between the hospital and physicians in the market; examples include outpatient surgery and/or imaging centers, medical office buildings, etc. Can also include joint ventures between small hospitals and larger hospital systems. Since joint ventures are used only for highly profitable services, the true “cost” to the hospital of this approach may be very great.

Venture Capital: typically used to fund innovative models/programs with the potential to be highly profitable and grow exponentially. Since most small or rural hospitals are trying to fund replacement facilities or other, traditional hospital services, this is usually not a realistic option.

Private Credit Enhancements

Credit enhancements offer credit‐worthy hospitals “cheaper” access to capital by lowering the interest rates applied to bonds or loans associated with the debt. Credit enhancements may be either private or public. However, these enhancements are typically not available to “make your institution creditworthy.” The two most common types of private enhancements are letters of credit and bond insurance.

Letters of Credit: Commercial banks can issue a letter of credit in support of a hospital. The letter of credit guarantees payment on bonds (or loans) in the event that the hospital is unable to make the scheduled payments. This allows the hospital to access capital at a lower interest rate. Typically, hospitals must pay the bank writing the letter on their behalf; the cost of the letter is variable, and based upon the bank’s perception of the overall credit‐worthiness of the hospital. In the case of small or rural hospitals, letters may only be available from local banks with which the hospital has an existing relationship – and this, too, may limit the overall amount of capital available.

Most letters of credit extend from three to five years, and must be renewed at that time. Bonds (and loans) often have terms in excess of 15 years, which puts the hospital at risk for renewal several times during the life of the bond or loan. If the hospital’s credit profile worsens after the initial issuance of the letter of credit, the renewal fees and covenants may be significantly more stringent, even unaffordable.

Private Bond Insurance: Similar to a letter of credit, bond insurance is a guarantee that the hospital will pay investors as promised under bond covenants. This guarantee allows the hospital to access capital at a lower cost than it could otherwise obtain on its own. Unlike letters of credit, bond insurance remains in place for the life of the bond. Several private companies offer bond insurance; however, very few independent small or rural hospitals can obtain bond insurance based on their own credit profile – which further explains the inability for small and rural hospitals to issue their own bonds.

Conclusion

This first article has explored private vehicles by which small or rural hospitals may gain access to capital. For most independent small/rural hospitals, private sources are not enough or are simply not available. Part II of this series will explore public sources of capital and enhancements to credit that independent, small and rural hospitals use with greater frequency, as well as tips for small‐hospital Board members facing decisions about different financing vehicles.

Recommended Reading

- “Financing Options for Nonprofit Rural and Community Hospitals.” Lancaster Pollard White Paper, October 2005.

- “Financing the Future II, Report 6: The Outlook for Capital Access and Spending.” Financing the Future III, Healthcare Financial Management Association, 2006.

- “How Are Hospitals Financing the Future? Access to Capital in Health Care Today.” Financing the Future I, Healthcare Financial Management Association, 2003.

The Governance Institute BoardRoom Press – September 2008

Marian C. Jennings, M.B.A., President, M. Jennings Consulting, Inc.

Amy B. Hughes, M.H.A., Vice President, M. Jennings Consulting, Inc.

› Download PDF

2 American Hospital Association Rural Health Care 2007 Annual Report.

3 Bill Henry. “The Rural Development Imperative: Fundraising to ‘Own’ the Hospital.”H&HN Magazine, 5/5/2008.

4 “How Are Hospitals Financing the Future?” 2003, Healthcare Financial Management Association, page 25.